We promised the other day when we showed you this lovely photo of Sally Antill taken by Jeni Reid that we would share some posts written by her during Wovember. Sally Antill and her other half – Michael Baxter – are breeding Soft Fell sheep. The idea is to produce a meat carcass acceptable to supermarket buyers while also yielding a fleece popular with hand-spinners. We will learn more about this in the coming weeks from Sally but by way of introduction, here is a wonderful post about how the unique fleeces of Sally and Michael’s Soft Fell sheep were involved in a fantastic community sheep to shawl event earlier this year, in Greenhead, Northumberland.

Wool on the Wall 2014, “Sheep to Shawl on the Wall”

It started as a simple enough idea.

Our local fibre group, Gilsland Fibre Fridays, offered to organise the spinning for the second Wool on the Wall event in nearby Greenhead. It’s a super event, very focussed on British – preferably local – wool in all its glory and versatility. Thinking aloud at the first planning meeting, I mulled over the process of getting from a fleece of a sheep through to a finished garment; I was thinking of perhaps a headband, a bookmark, something small, feasible to complete in a few hours. People could enjoy all the steps involved in getting from raw fleece to finished item in a day and have something to take home at the end!

However when one of the organisers lilted “Sheep to Shawl on the Wall” and everyone’s faces lit up I realised that somehow or other, we were going to have to make a shawl in 6 hours. From fleece.

We decided to use one of the fleeces from the sheep on my farm. It’s about as local as you can get for Wool on the Wall – these girls graze the pastures alongside Hadrian’s Wall at Birdoswald Roman Fort. They’re commercial sheep, producing good north country fat lambs for the likes of Tesco, Asda, Morrisons, and our local butcher. They have a very spinnable fleece – the subject of which will be explored in a future WOVEMBER post! It’s of a staple length and character that mean it can be carded or combed, or flicked and spun from the lock, with equal ease. It’s not superfine, like Shetland or Bluefaced Leicester, but it’s plenty soft enough for a hat, a jumper… or a shawl.

Traditionally ‘back to back’ – sheep’s back to human’s back – events are undertaken on raw fleece, fresh from the farm. There are competitive events where teams of 5 to 9 highly-skilled people process the fleece into a shawl, a waistcoat, even a jumper. However, none of us had ever done, or even seen, one of these events; none of us felt we were in the ‘fastest spinner’ or ‘fastest knitter’ category. Also, we wanted to use this to event to demonstrate the process, which meant taking time to talk to people about what we were doing, let people have a go and so on. We knew we needed as many spinners and knitters as possible to participate if we were to have a chance of making any kind of shawl in a day.

We wanted maximum participation, and because not all spinners are prepared to spin raw fleece on their spinning wheels, and not all knitters will enjoy knitting ‘in the grease’, we decided to wash the fleece. There’d be a fleece ready to use – washed but otherwise untouched – and we’d clip a sheep to show that part of the process. Our plan was that as soon as the sheep was clipped, we could start processing the pre-washed fleece.

At this point the fleece from our commercial sheep had already found a small, select fan club. I’d spun it myself, of course, and would select a few really nice fleeces each year to show to local spinning groups at Open Days. I’d offer these for sale, usually in aid of club funds. One or two each year would be bought, and each year I would have a few left over which I would put into the sacks for the Wool Board the next summer when we clipped the sheep again. (Clipping is the same as shearing; we call it clipping around here.)

In truth, it did puzzle me a bit that not all of these lovely fleeces sold; the people that took them always said how much they enjoyed spinning them. Never mind; there’d be more having a go with it this year! A fleece for the Wool on the Wall event was selected and washed for testing. We took it to the next meeting of the Stanhope Spinners in County Durham.

We tipped up the sack and the beautifully clean white fleece tumbled onto the floor in the centre of the room. As the locks opened and the soft crimp caught the light, an ‘ooo’ and a lifting of bottoms from seats could be heard. ‘What is it?’ someone asked. I replied “it’s one of our commercial fleeces. For Wool on the Wall testing.” We divvied up the fleece amongst the volunteers and over the next week or so, it was carded, combed, spun, plied and knitted in a number of homes on a number of wheels. We reconvened later to review our findings.

The end result of all this was that we decided to knit singles – a single strand of yarn, not plied with another to make a ‘balanced’ yarn – and to compensate for the bias this would introduce by knitting in garter stitch. For speed we used large needles, and found that with these knitters and spinners on these needles, the additional knitting time for garter stitch over plain stockinette was less than the additional time for plying. The singles knitted in garter stitch on large needles made a rather delightful, airy, lacy-looking fabric – perfect for a shawl.

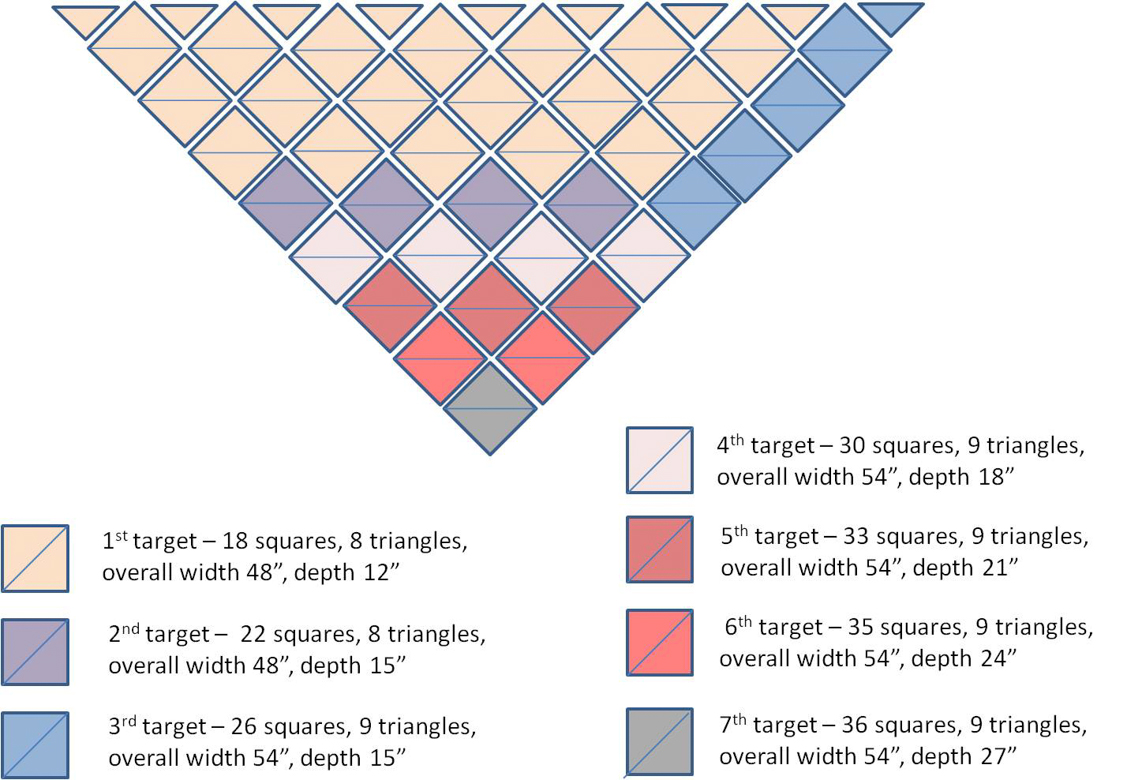

Our timings confirmed what we’d already suspected – as long as we could get enough spinners, we’d be fine for the spinning. It was the knitting which would be the most time-consuming aspect of the challenge. We decided to construct the shawl from 6” squares, and produced a design which gave us the flexibility to make a 4’ wide shawl of 18 squares and 8 triangles (half squares), or to make a progressively larger one, up to a maximum 54”-wide one of 36 squares and 9 triangles, if we had the time and knitters to do so.

One square took approximately ½ oz yarn to make. An average knitter took 40 mins to an hour to knit the square; an average spinner about 20-30 minutes to spin the yarn for one square. The test fleece we were using was a delight to spin; it needed little or no preparation, just a light comb of the tips of the locks and spin directly from the lock. However some spinners preferred a carded preparation, so we planned for volunteers to card, on hand cards and on drum carders, for those who would prefer to spin from rolags or batts.

By now word had spread, and people were signing up to come and join us from all the surrounding counties. Members of the nearby Guilds – Eden Valley and Tynedale – from Durham, Dumfries and Bradford and from of all the local spinning groups. Even spinners from as far afield as Edinburgh and the West Midlands wanted to come – spinners do love to spin with other spinners! We even managed to attract two people who had participated in back-to-backs before; one had even been in the winning team a few times.

Assured now of sufficient spinning capacity, we set about recruiting knitters from local knitting groups. For those who hadn’t knitted with energetic singles before, we tried to give them some freshly-spun yarn to practise.

All this time I’d known that we would be spinning ‘on the Green’ in Greenhead, but wasn’t exactly sure what was meant by ‘the Green’. Rather late in the day I discovered that ‘the Green’ was in fact a large verge on a corner in the centre of the village. Not very large – and not a flat surface. With trepidation I told the organising committee that we now had so many makers coming that there was no way we would all fit on this corner, and that we’d need a flatter surface suitable for operating a plethora of incoming spinning wheels!

Thankfully the Parish Council agreed to let us use the Millenium Green, a lovely large flat green opposite the school, and the National Park kindly lent us their large marquee so that we could keep the spinners and their wheels protected from any rain – always a consideration, even in mid-July, in Northumberland.

By now two things had happened. Firstly, through the Sheep to Shawl event, a lot of people had spun our fleece and discovered that they loved its character and hand – some of those unsold fleeces were now happily sold. Secondly our wool now had a name – Soft Fell – reflecting its origins in the hill sheep of north Cumbria and Northumberland, and in careful breeding designed to create an animal with a nice fleece, capable of producing and rearing good fat lambs outdoors on the Cumbrian upland rough pastures. (The story of breeding Soft Fell sheep will be the subject of a subsequent article.)

Meanwhile in Greenhead on Sunday 13th July 2014, the marquee was up, the sun was shining, my other half – Michael Baxter – had a small pen of sheep to clip with hand shears, (better for spinning and more of a spectacle for the visitors) and as the spinners arrived and set up their wheels, taking us quickly over my calculated 14 minimum, I began to relax and enjoy the day.

All our preparations paid off; the spinners knew the fleece and how to spin it, the knitters came prepared with the right size needles and knew how to knit the squares, the sewing-up team had a plan and began construction as soon as the first four squares were finished. A hiccup due to the actual fleece having ‘sticky tips’ (it was a first clip fleece, and sometimes the tips of locks of a lamb’s fleece, having never been cut, are less ready to separate than the tips of an adult sheep’s locks) was soon worked around – spinners got busy with the dog combs they had brought with them, opening the tips with a few strokes, and helpers got busy driving drum carders to make big airy batts.

All around the village and at the stalls in the vendors’ area and in the farmers’ market, there were people knitting, a bobbin skewered on a knitting needle held firm in an empty shoebox at their feet, or a project bag hanging from their arm with a centre-pull ball of lively yarn feeding from it to the needles in their fingers. Most of the wheel spinning took place on the Millenium Green, while spindlers wandered from Green to stalls to shearing display, creating and winding yarn on their spindles as they went.

By 2pm it was clear we would make a shawl worthy of the name, and on the dot of 4pm it was complete.

Produced under such time pressure and by such a diverse range of people at all skill levels, we were not expecting a finished article of great consistency or technical competence, but rather one of rustic charm. And so it was. The surprise was in the affection and connection felt by all for and to this object – of course by the spinners, knitters and sew-er-uppers who had made it, but also by the community who had watched it all unfold and the visitors to the event who became caught up in the atmosphere of collective endeavour. The significance of the shawl lay in the way its construction had been witnessed and shared by so many people. To quote one of the organisers, “It was quite hard to see it leave the village after so many people had been part of the making of it, contributing to its character and texture.”

Thanks so much to Sally for sharing the story of this special shawl and the people and animals involved in its creation! Thanks also to Marjorie, Fiona and Elaine for their wondrous photos. Text © Sally Antill and photos © Marjorie Baillie, Fiona Curtis and Elaine Hill and shared with kind permission.