This post was curated by Paula Wolton for our Woolness and the Land theme and features the voice of Sally Vergette. She explores the pain of the Foot & Mouth crisis of the early 00s, and the role that working with wool played in aiding her recovery from this devastation. Both this post and the one we shared earlier this morning speak to the intertwined fates of individual Woolness, and the Woolness of the Land.

My husband and I came to live at Coombe Farm in 1988 because we were artists and needed affordable workspaces. The land is beautiful with old orchards and wild flower meadows. We had a small flock of our local breed of sheep, Devon Closewools, that thrived on our herb rich pasture.

Then they were all slaughtered in the foot and mouth epidemic of March 2001. It was a deeply traumatic experience.

All we had left were a few sacks of their beautiful wool from the previous shearing. The trauma left me unable to continue my painting career, but I wanted to make something again, so I learned to spin and made dyes from the plants around the farm and knitted jumpers which I sold, making enough money to restock the farm with 20 lovely Devon Closewool ewes whose descendants graze the farm today.

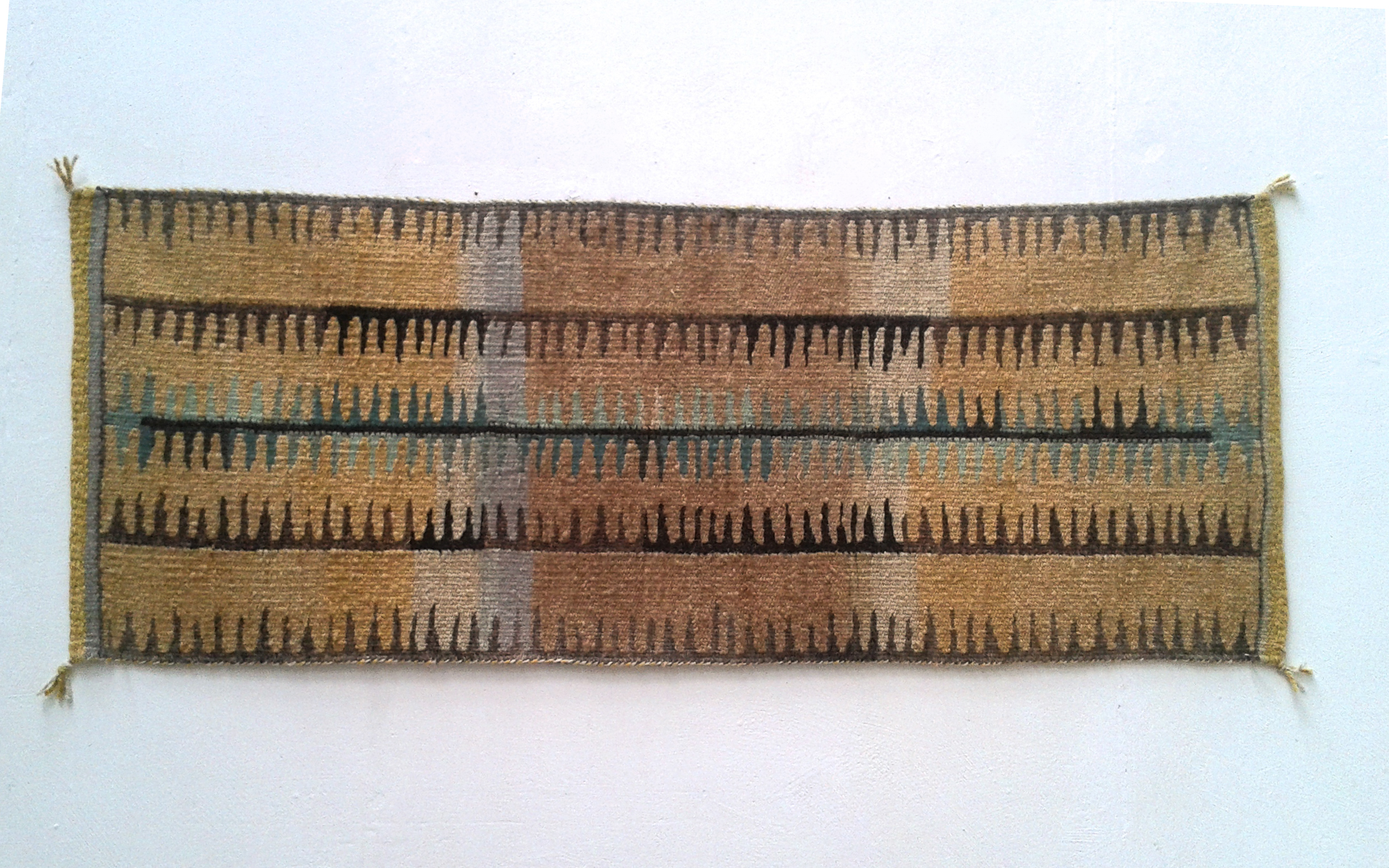

I now make rugs on a Navajo loom.

Everything is from the farm, including the warp wool, and all completely handmade by me.

The rugs and jumpers take ages to make but I hope they take a message of warmth and hope [both practical and metaphorical] into the world beyond our gate.

Making them certainly gives me joy.

Important Information: images and text © Sally Vergette.