This evening Paula Wolton has enlisted the help of her husband Rob Wolton – an experienced ecologist and environmentalist. Paula has worked alongside him as her partner in life and farming for 30 odd years which has led to heated discussion and interesting compromise from which she feels both have learnt and grown. In curating this piece, Paula wanted to emphasise the need for growth and learning in relation to wool and land-management. We at Wovember are really grateful for a perspective on creating balance between grazing and the health of the land from someone far more qualified than us to comment on this important topic. We hope this piece will generate some positive and thoughtful discussions about grazing and ecology: something we must surely consider in our contemplation of this weeks’ theme: Woolness and the Land.

Wool – good or bad for nature?

It’s all a matter of the right sheep, in the right places, in the right numbers. At least as far as wool and wellness of the land is concerned. To be fair, the same applies to our other domestic grazers – goats, cattle and horses.

Sheep are not native to the British Isles – no breed or indeed any ovine species was ever indigenous here. The same applies to goats. True, domesticated sheep and goats were introduced to this island a long time ago – by Neolithic man, some four to six thousand years ago. But, in an evolutionary time scale, that is just the blink of an eye. The point is that our native flora has not co-evolved with the either sheep or goats. As a consequence it cannot be assumed that these animals will be in balance with our wildlife even in the feral state. Indeed, both managed and feral flocks seldom are and can cause a lot of damage.

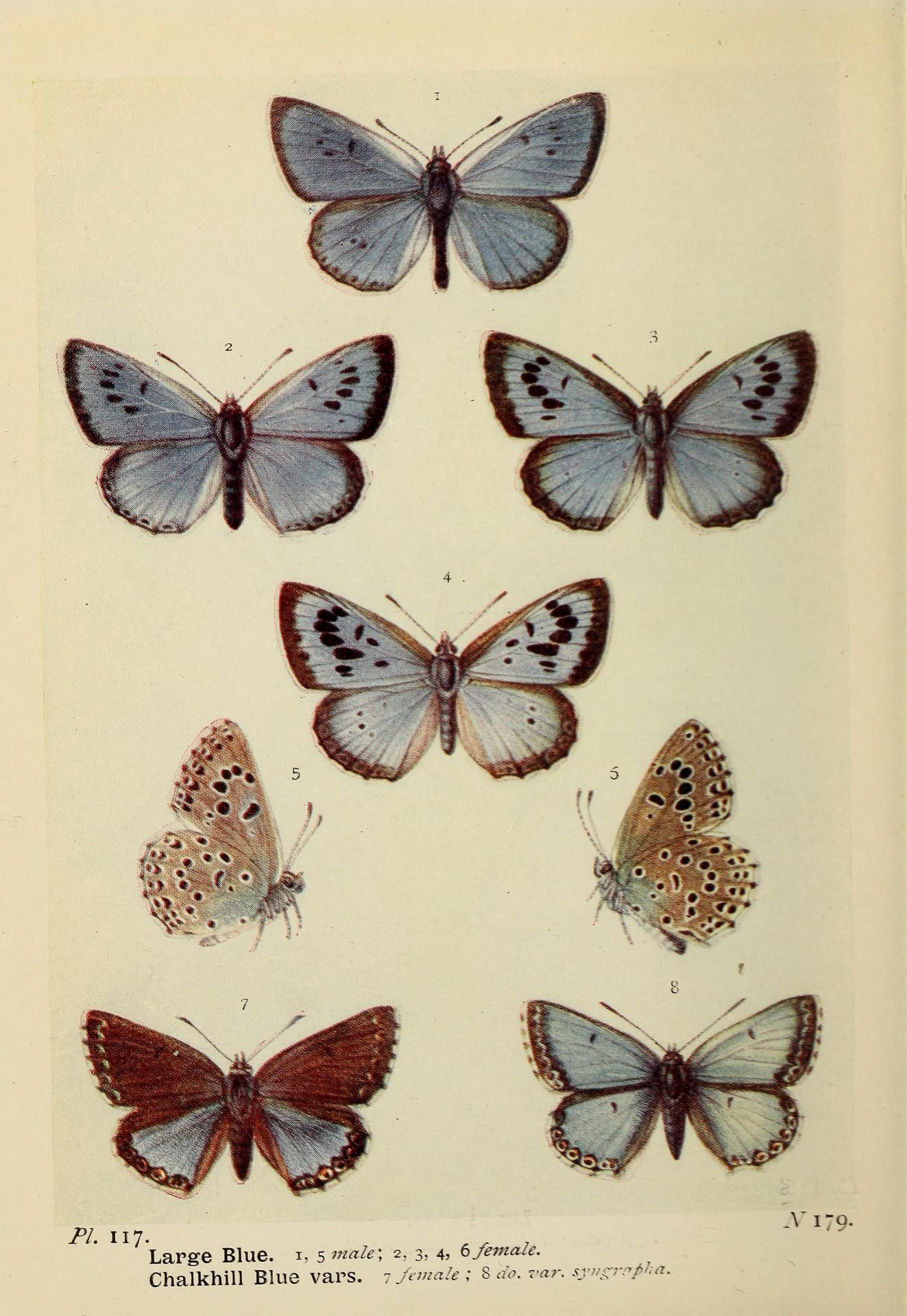

Not that they are always bad for the land. Far from it. Sheep are highly valued for the benefits they bring to some wildlife habitats. The prime example is lowland limestone or chalk grasslands. Here the large expanses of turf man has allowed to develop through the clearance of woodland, as on the Downs, is remarkably flower-rich (if spared the plough, fertilizers and herbicides). Such grasslands need to be grazed closely at certain times of the year, and sheep are ideal for this. Without sheep we would not have those wonderful displays of wild flowers with clouds of chalkhill blue butterflies. But even here numbers have to be managed carefully so they are in tune and balance with the flowers.

The greatest problem arises on our uplands. Here large tracts of moorland have been turned by sheep into endlessly boring expanses of closely grazed grass. This may make it easier for human walkers to stroll across the hills, but for wildlife it’s disastrous. Few insects, birds, native mammals or indeed any other wildlife can thrive under these conditions. Examples are the hills of central Wales, the Southern Uplands and parts of the Lake District. High numbers of sheep have obliterated heather and most other plants in these areas. The land has become sick because of them. Numbers need to be reduced substantially, at times to zero, to allow the land to recover. George Monbiot in his book Feral is a powerful proponent of this.

Saltmarsh is another habitat that is often ruined by sheep. Heavy stocking leaves nothing but a uniform short turf and eroded tidal creeks and channels. Wild geese may sometimes join the sheep, but most wildlife is banished to the edges. The lamb may taste delicious, but it comes at a high environmental cost.

“Native” breeds – those that have been developed in the British Isles through centuries of artificial selection – are often hardier than others. Sadly this does not mean that they are any less damaging if grazed in the wrong place – to the contrary they can make matters worse precisely because they are able to graze less palatable plants, or those in difficult to reach places. Even our primitive breeds, the Soay, Boreray, Hebridean and North Ronaldsay, put native vegetation at risk if not kept under careful control.

Sheep can be healthy for the land, or can be as a disease to it. Too often the wool we use to clothe ourselves, and the lamb we eat, impoverishes the land, sometimes ruinously. Better informed and smarter choices, whether as producers, consumers or tax payers, are surely what’s needed. Only then will wool and land wellness go hand-in-hand.

Important Information: text © Rob Wolton.