To round up our “Working with Wool” phase of WOVEMBER and to set the scene for the last and final theme for our month-long celebration – “Wearing Wool” – we have a Q&A with the founder of Keep & Share, Amy Twigger Holroyd. Keep & Share is the umbrella term for Amy’s research, knitting activities and fashion label.

100% WOOL Gladys Cardigan, designed by Amy Twigger Holroyd and knit on knitting machines in the Keep & Share workshop, photo by Amy Twigger Holroyd

Designing and creating clothes on knitting machines in the Keep & Share workshop; participating widely in the culture of knitting and crafting events; researching the meaning of hand-making our clothes for well being and fostering approaches to fashion which are sustainable, Amy is an enormous force for change in contemporary fashion! Her work with wool ranges from “hacking” sweaters to presenting papers at knitting and mending conferences, to organising participatory knitting projects to teaching people to knit and crochet at public events.

Taken together, Amy’s fascinating doings address many of the issues which relate in one way or another to the aims of WOVEMBER such as slow fashion and sustainability; the meaning and value of our clothes; the properties of WOOL; and the need to explore fashion in relation to wider social questions. Amy kindly agreed to do an interview with WOVEMBER about some of these mutual areas of interest… for further details on Amy’s distinctive, joined-up approach to her work, please visit her amazing website…

1. Last year during Wovember I kept thinking about the slowness of wool – how long it takes to grow wool, to turn it into textiles, and to then fashion clothes from it – and I was deeply disturbed by the imbalance between the natural timings of that process and the speed with which our High Street shops churn out garments. I founded a personal project called The Slow Wardrobe as an antidote to the speed of mass production and mass consumption. The idea was that in approx. 10 years time, I will have made or found or been given most of the clothes I’ll ever need, and that these will mostly be made from wool. Obviously me being me and this being Wovember, sheepiness is key to my personal take on The Slow Wardrobe. However, I am extremely interested in how other practitioners are working with the concept of slow textiles. What does “slow fashion” mean to you? How is it different from “fast fashion”?

My own epiphany about slowness came about ten years ago when I was doing my MA. I came across an article in a trend journal, View on Colour, suggesting that, in sustainability terms, “the more definitive solution is to keep” and that “putting together a wardrobe and a home will become a life-long process and something of a quest”. The idea really appealed to me and became a strong influence on my work. I started looking at how we could gain satisfaction from our garments, and from our experience of fashion, without creating the almost inconceivable amounts of waste produced by the current system.

As a designer, I think about how I can design garments that people will want to keep, and continue to be satisfied by. I think about creating an interesting (and genuine) story behind the product, and having a direct relationship with my customers. I also try to design garments which can transcend passing trends, without being too ‘classic’ – my strategy is to combine archetypal details with unconventional means of construction (I’m obsessed with seamlessness).

I still believe in genuine trends – shifts in collective taste – and that these trends reflect and respond to shifts in society and culture more broadly. But I’ve long been of the view that this tendency has been hijacked and accelerated by big business, aided by the homogeneity of our high street.

So, I suppose to me slow fashion isn’t just the opposite of fast fashion – it’s about savouring the most enjoyable and satisfying bits of wearing clothes, and celebrating the practices around them: making, wearing, mending. It’s about starting to identify which bits of fashion are accelerated, and stress us out, and which bits bring us joy and play a genuine role in connecting us to each other. It’s not trying to get rid of fashion, but rather to dwell more intensely on why we like what we like (which might change over time), and to embrace stories of making as part of the spectrum of things which engage us with our clothes.

2. Could you give an example of a slow fashion approach that cannot be rushed – i.e. something which takes time and which is especially important to the activities of Keep & Share?

Until a few years ago, I created a new collection every 6 months for Keep & Share. Although that schedule was in keeping with the timetable of the fashion industry, it felt to me reasonably slow (especially compared to the high street where new stock arrives continually). It allowed me to enjoy the gradual process of gathering inspiration and translating into a new collection, with shape and detail ideas evolving from one season to the next.

However, this year, I’ve taken a further step in the slow direction, by creating a more permanent collection of pieces which have become Keep & Share classics – and then creating an archive of over 150 designs from the earlier collections. Customers can now commission a piece from the archive, choosing their own colours and yarns and tweaking the design if they wish. It means that I’m not continually pushing forward, but can also look back at all the work I’ve done over years, and to let those pieces ‘live on’. I’m showing that I don’t think they’re out of date, or not longer relevant. But because there’s such a choice, it’s up to the customer to find a piece that appeals to them in today’s context. That seems pretty slow fashion to me.

3. Do you think that taking more time to clothe ourselves has tangible benefits?

Good question – yes I do, and that’s the broad question behind my PhD research. As a maker, I tend to think of making – and particularly making clothes – as a positive and rewarding experience. Having run knitting workshops for several years, I began to realise that although some people share that experience, for others making clothes can be more ambivalent. And when I thought about it more, I could identify with that too! I’ve been making clothes since I was a teenager, so I have lots of examples of things not quite turning out how I expected, things going wrong at the last minute, the tears of frustration when you can’t get something just right.

The general idea behind my research is that if we were to make and mend more of our own clothes, that could carry benefits in terms of both individual wellbeing, and for sustainability more broadly. But there’s hardly any research about how it feels to wear things you’ve made in a culture where the majority of clothing is mass-produced. I’m in the middle of the project, so haven’t got any conclusions yet – but I think it’s safe to say that the experience can be both positive and negative!

As part of the research, I’m trying to explore whether a designer-maker might be able to support people in their own making and mending, to make the experience of wearing those clothes more dependably positive. This links to my thinking that a slow fashion label could not just produce clothes, but provide support and assistance in making and wearing practices.

4. Obviously because this is Wovember, we are all about celebrating WOOL! I notice that you use wool to produce some – but not all – of the garments that you make in your workshop for Keep & Share. I wondered if you could talk about some of the unique properties of the wool that you use, and what types of garments you would specifically use 100% wool for? I also wondered if you could talk a little bit about where your wool comes from and some of the creative ways in which you minimise waste from the industrial spinning process such as producing yarn from offcuts?

I only work with natural fibres, and have a preference for animal fibres: wool, alpaca, cashmere. I find wool to be friendlier to work with (than, for example, cotton) – and I love the way it has this almost magical relationship with steam, to set it into place.

I’m interested in the story behind a yarn, as this can add to the story behind the garments I produce – but have to balance much more practical considerations such as the colours available, the minimum orders, the price and so on. As a small producer placing small orders, I often have to choose from a rather restricted range of yarns. So, I tend to get my yarns from a range of places – some from an Italian spinner that produces beautiful quality yarns, some from mill shops who sell quality, but limited quantity, remaindered yarns, and some from smaller UK producers.

Because I’m trying to create pieces which will be kept for a long time, I want yarns that will age well – like wool – but the yarns have to have a delicious handle. From talking to customers, I know that’s of prime importance to them – I really feel that there’s no point in making a garment if no-one will want to wear it!

I try to avoid waste in my practice, and so some years ago started winding the smaller quantities of yarns which were left over from my collections into my ‘Offcuts Yarn‘ – a stranded chunky hand-knitting yarn. Each one is limited edition – limited by the amount of the ingredient yarns – and the colours change depending on what I have left over.

5. In your practice you often “hack” the stitches of an existing garment, reconfiguring the knitted fabric to spell out features of the garment normally hidden from sight, such as the details contained on the garment label; I have become especially interested in garment labels since launching Wovember, as the laws about labelling garments are much stricter than the laws regarding how garments might be described for online search engines. For me what I am most interested in finding on old garment labels is “Pure New Wool” or “All New Wool” or “100% Wool”, and these are details I look for when purchasing second hand clothes for The Slow Wardrobe. I wondered what details on existing garment labels are especially interesting to you and which label details you have been inspired to work into various stitch-hacking projects?

I suppose I have two different approaches.

I look out for older garments and use my hacking to elevate the details of the original manufacturing process. For example, the old woollen jumper I found – made by ‘Jayfor of Auchtermuchty’, made in Scotland. The label seemed to sum up the fact that it was so old, and came from a different time.

‘Jayfor of Auchtermuchty’, made in Scotland; old sweater, stitch-hacked and photographed by Amy Twigger Holroyd

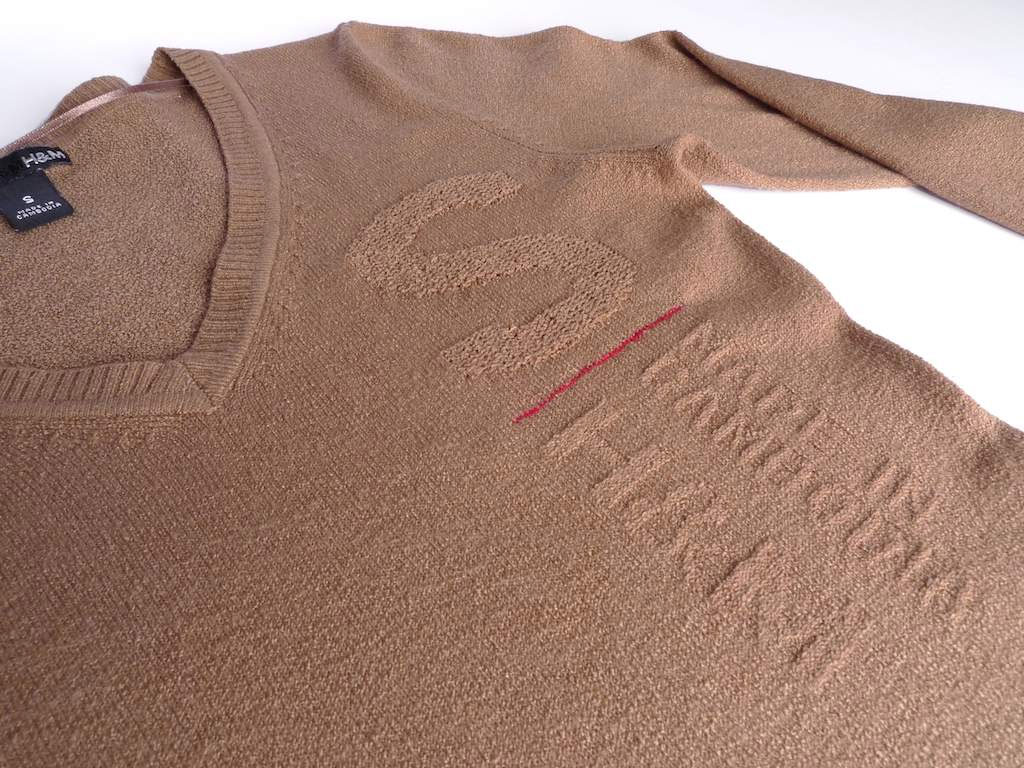

However, most of the pieces I’ve hacked have been newer, mass produced things. I’m interested in how using a very time consuming process to hack that information into the cloth might make you think about its original manufacture.

One aspect is where it’s made, and thinking about that. A H&M jumper I hacked was made in Cambodia.

Amy’s stitch-hacked H&M jumper, photo and stitch-hacking by Amy Twigger Holroyd

I’ve done a couple of slightly older M&S pieces, which were made in the UK. Spending hours hacking the country of manufacture into a garment really makes you think about it!

I also like codes and sizes, partly just as typographic features and partly because it gives me a sort of ‘I am not a number’ feeling – it makes you realise how many would have been produced.

The fibre question is interesting – I have hacked non-natural fibre ones as exhibition pieces but wouldn’t want to wear them, I don’t like wearing clothes made from oil! So if I was hacking for myself, it would be the fibres I enjoy wearing – like wool – that I would spend the time on.

Amy Twigger Holroyd’s first stitch-hacking project – a sweater knitted (perhaps?) by Amy’s Grandmother, and reconfigured by Amy Twigger Holroyd

Many thanks to Amy Twigger Holroyd for sharing these insights into your work with WOOL! We are especially excited here at WOVEMBER to see how some of your approaches to fashion relate to the rest of WOVEMBER and our focus from tomorrow onwards on aspects of Wearing Wool! All content unless otherwise stated © Amy Twigger Holroyd, originally published on the Keep & Share website, and used here with kind permission.