WOVEMBER readers may have noticed that all three members of TEAM WOVEMBER have visited Shetland, and have fallen a bit in love with these amazing isles! In the first year of WOVEMBER, Kate put together a beautiful guest post featuring “Ooey Ollie” talking about grading and sorting Shetland wool fleeces; last year we did a Q&A with Kate about her wonderful book, “Colours of Shetland”, and this year, throughout WOVEMBER, Tom and I shall relate some of our experiences of being in Shetland this October for Shetland Wool Week.

Shetland Wool – perhaps more than any other type of wool grown in the UK – is strongly connected with its roots in the working Shetland landscape. Although the Shetland sheep breed is grown in different places around the UK, (and indeed all over the World) it evolved to survive in the specific geography of the Shetland islands. Here, the Shetland sheep retains its connections with the traditional crofting lifestyle which kept the breed going for hundreds of years, and with the knitting styles which exploit the wonderful crafting opportunities offered by its distinctive wool. The fleece of the Shetland sheep – resilient, soft, bouncy, light, warm – is the foundation for outstanding textiles which have made Shetland famous the world over. From historic textiles held in the Shetland Museum & Archives and the Shetland Textile Museum through to the beautiful creations of contemporary makers like Ella Gordon, artisans have made – and continue to make – amazing things out of Shetland wool. At WOVEMBER we are particularly passionate about understanding the provenance of woollen textiles, and in this post which originally appeared here, we explore the source of Shetland Wool: Shetland sheep. We focus on the Ram sale, because – as Diane wrote in 2011 – “the actual source of all those woolly balls… begins on a crisp autumn day… with a cool breeze blowing… leaves crunching underfoot.. and the knowing sparkle in the eye of a ram”…

One of the best things about Shetland Wool Week is that it provides rich opportunities for discovering the people, animals, landscapes, history and labour behind Shetland Wool. The events programme offers folks the chance to really appreciate its origins in a distinctive place and culture, and from a specific breed of sheep.

The Flock Book Fine Fleece Price Giving at the Shetland Rural Centre on Saturday is one of the highlights in the programme if you are especially keen on discovering the animals behind Shetland Wool! Here, you can meet Shetland rams, and watch the presentation of the annual prizes for Fine Fleece on the Hoof. You can also see rams and ram lambs being auctioned off to Crofters and Farmers looking towards next years crops of Shetland fleece and lambs.

I loved my day at the Mart. Meeting the sheep emphasises how the little balls of Shetland yarn I like to knit with start out as living fleece on the back of a sheep in all the wind and rain and weather.

This transparency – understanding the origins of wool on actual sheep – is important; but there is a deeper joy involved in meeting the sheep, too. They themselves with their faces, sounds, smells and behaviour are a source of inspiration as well as wool.

I am clearly not alone; many things spotted in Shetland make explicit, celebratory references to sheep.

Meeting sheep is one important step in closing the gaps between producers and users of wool, however the journey from sheep to shoulders is long and complex. Ambassadors to explain some of the intermittent stages along the way are vital for promoting better understanding between Crofters, Farmers, Knitters, Weavers, Spinning Mills etc. And few folk do more during Shetland Wool Week to explain how raw fleece gets turned into usable products than Oliver Henry.

I’ve never met anyone as close to wool as Oliver seems to be. His pair of hands is the first that raw Shetland fleece passes through on its way to the scouring and spinning mill, and he is directly and literally in touch with all of the Crofters and Farmers selling fleece to the Shetland Woolbrokers. However he also does an amazing job of speaking about the work of grading and sorting fleece to the public, and takes a really keen interest in the end products that are produced from Shetland wool (including the handknits that knitters produce). I loved listening to some of Oliver’s talks during Wool Week, and Jane Cooper has written a really lovely piece about Oliver’s talk at the Auction Mart with great images of him holding up finished products and raw Shetland fleece, describing all the stages in between those two things.

From Oliver, I learned the lovely word for a very rough fleece: scadder.

I adore SCADDER in all its hairy glory; to me it is the wildest edition of a Shetland sheep’s fleece, and conveys a marvelous sense of soil, earth, rock, stone and weather. I wouldn’t knit knickers out of it, but I bet it would make amazing felted bowls, table mats, rugs or an outer wrap; It has structure, character, resilience and liveliness.

There are finer grades of wool in The Wool Store, though, (in fact scadder is apparently getting rarer) and along the spectrum of the different grades, you can see the influence of scadder to a greater or lesser degree.

This fine fleece has far fewer guard hairs than the scadder, and you can see the tiny waves – the crimp -responsible for its bounciness. It could be finely spun to make beautiful lace, or used to knit scarves, mittens, or anything that will be worn close to the body. It’s amazing that both this and the very rough stuff can be found on Shetland sheep, but that variety is part of what makes Shetland wool special.

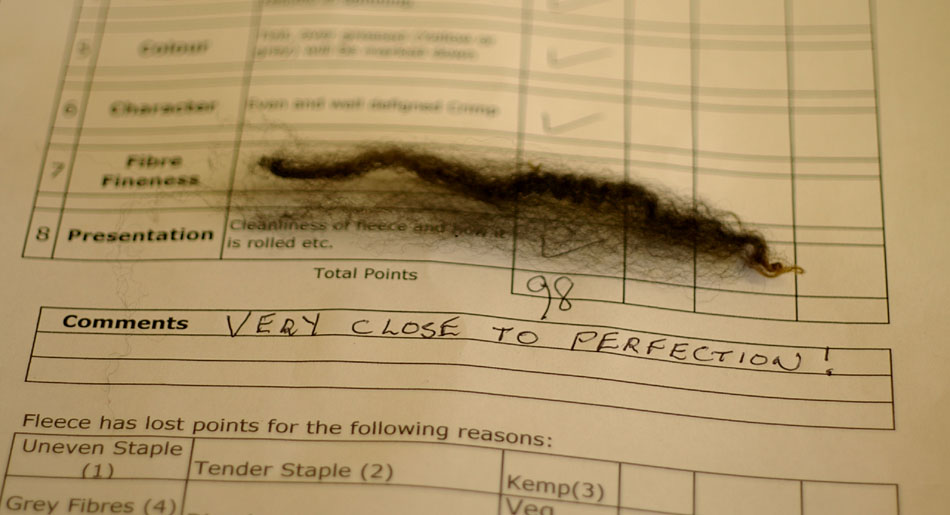

At the very top end of the scale is the Champion Fleece, which – this year – was an extremely uniform, soft, crimpy, beautiful thing of wonder grown I believe by Adie Doull.

I am really excited that Tom and Jane jointly purchased this special fleece and will be spinning and producing something from it. I am also really excited that they paid twice what was intially asked for this fleece: to me, this proves the value of allowing folk to understand where wool comes from. One of the best thing about closing the gaps between producers and growers of wool is that when you can discover the people, animals, landscapes, history and labour that are behind Shetland Wool for yourself, it gets easier to appreciate its real worth.