“I didn’t say I knowed of a shepherd,” said she….”That’s where you’ve took me all wrong. I said I knowed of one trained to the work for more’n twenty years, as ‘ud be real glad and ready to come to ye this very minute. ‘Tis myself, Mr. Wilverly. Give the flock to me and old Airibella here, and ye’ll ne’er have cause to rue it”.

: : : :

When I first met up with Southdown shepherd David Burden in 2011 to talk about his flock, it quickly became clear that we had a lot in common. We share a love of Southdown sheep, the South Downs and the people associated with both. Unlike me, David has a wonderful memory making him a natural storyteller, and I love to listen to him telling a good yarn.

One day David mentioned a name I had never heard of, a Mr Edward Tickner Edwardes, how he had written a story about a shepherdess, and how local people had a theory about who the novel was based upon. This is the tale of how looking for my local wool led me to discover an out-of-print novel, a long forgotten silent black-and-white film, an equally neglected real life shepherdess, how everything is connected, and how I still get a thrill when I think about Tansy. [Warning: this article contains spoilers!]

Edward Tickner Edwardes (you can see a photographic portrait here, and a painted portrait here) was born in London in 1865, and by all accounts wanted to be a writer from an early age. I am not sure what date he left London for the then remote Sussex village of Burpham near Arundel, but here he lived for much of his life. Here, he also wrote about his walks on the South Downs, the local wildlife and change of seasons, as well as village life.

His initial articles were published regularly in magazines like The Pall Mall Gazette, the Globe and the Echo with his first book of non-fiction published in 1898. As well as writing, he kept bees and his study ‘The Lore of the Honey-Bee’ published in 1908 is the work most associated with him today, among the few who still know his name.

It is with his second novel Tansy published in 1914, where my interest in Tickner Edwardes begins in earnest. The novel was reviewed very sympathetically by The Spectator as ‘an eclogue of a sheep farmer’s life’. What’s interesting to me about this is that the magazine did not use the word shepherd or shepherdess, preferring instead the ungendered noun ‘farmer’. I wonder was this because the author of the review could not decide which term to use, or did not want to use either term thinking it may put off potential readers, or was it because despite the novel’s title the reviewer felt the story centres on Tansy’s employer, farm owner Joad Wilverley?

These speculations led me to look a little closer at the novel and the use of the terms ‘shepherd’ and ‘shepherdess’ when I re-read Tansy earlier this year. The book employs both to describe Tansy, with particular characters using one or other, though never interchangeably. Up to the point at which Joad Wilverly decides to take on ‘a woman for a shepherd’ the feminine form has not been used. This is not surprising; as the novel opens the current shepherd of Fair Mile Farm ‘old Varlick’ is male.

With the ill health of the incumbent shepherd and the death of her father Tansy makes a plea to Joad Wilverly to take her on (see above for the full quotation). Tansy herself uses the substantive form in such a way that she is then able to associate herself with it: “I didn’t say I knowed of a shepherd…‘Tis myself.” Importantly, she appears to be making a clear personal distinction between the denomination of the role from the experience she has of the work of looking after a flock.

Having agreed to take Tansy on, the next chapter begins by directly avoiding using the term ‘shepherd’ at all:

The strange news of the appointment of a woman to the charge of the flock at Fair Mile Farm supplied the principle subject of talk in G [the village] for the new few days; but almost unprecedented as the thing was in the whole history of the South Downs, it partook somewhat of the nature of an anti-climax, following so soon after the more stirring events in connection with the death of Tansy’s father.

Tickner Edwardes seems a little unsure of himself here. Whilst acknowledging the ‘strange’ even ‘almost unprecedented’ nature of the appointment, it is then dismissed as an ‘anti-climax’. On second reading, I like to think that this apparent ambivalence is a mechanism employed to discourage readers from making assumptions about traditional stereotypes.

The only character in the novel who gives expression to an overt parody of the pastoral notion of a shepherdess is Joe Heaver a local labourer who encounters the narrator in the village inn: “I seed a ould picture once…as wur full o’ shepherdesses all in a kind o’ flower-garden, wi’ blew ribbins to their hooks, and sech high petticoats as would never do i’ this windy country”. Joe’s observations about shepherdesses stand out in the novel as romantic folly with a definite touch of comic absurdity.

The next mention of the role is the first time the word shepherdess is used and is spoken by the only other female character Minella (the narrator’s love interest):

I like this business of Tansy Firle turning shepherdess… Who could help liking it? – from the feminine point of view at least. It’s a fine thing, Tom, for a woman to take the initiative, by reason of her own competence, in affairs where, as a rule, men alone have any say.

From this point forward Tansy is referred to as ‘shepherdess’ by all who come to know and admire her as a person, with one notable exception: her employer. Joad Wilverly addresses her directly as ‘shepherd’ both to commend her, and when he dismisses her: “My brother and I have decided not to keep a head-shepherd on the farm any longer”. His use of the word remains rigidly within the framework of the business of shepherding.

Whilst Tansy is clearly not a feminist novel, it does address double standards in morality, gender roles and class politics at a time when many were refusing to acknowledge the growing call for political and social equality across genders.

Less than a year before publication, in July 1913 members of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies from the nearby villages of Ford and Littlehampton took part in a country-wide suffragist march with members joining tens of thousands of women from across Britain who walked to a meeting in Hyde Park to demand voting equality. The marches attracted both local and national press coverage and it seems unlikely that Tickner Edwardes, a regular contributor to popular London magazines and the Sussex press would have been ignorant of these events.

I have come to believe that Tickner Edwardes purposely uses certain characters to deploy either the feminine or masculine noun throughout the novel in order to create a distinction between the person, the ‘shepherdess’, and the job of the ‘shepherd’. In this context one term is not being privileged over the other: one is who Tansy is, the other is what she does. In today’s more gendered nuanced age these binary opposites and the language that connects them may feel conservative but within its historic and geographic context could be construed as progressive.

Whilst the novel was popular immediately after its publication, what made Tickner Edwardes a familiar name to a wider audience after World War One was a film adaptation of the book, with Alma Taylor one of the most popular actresses of her time, cast as Tansy.

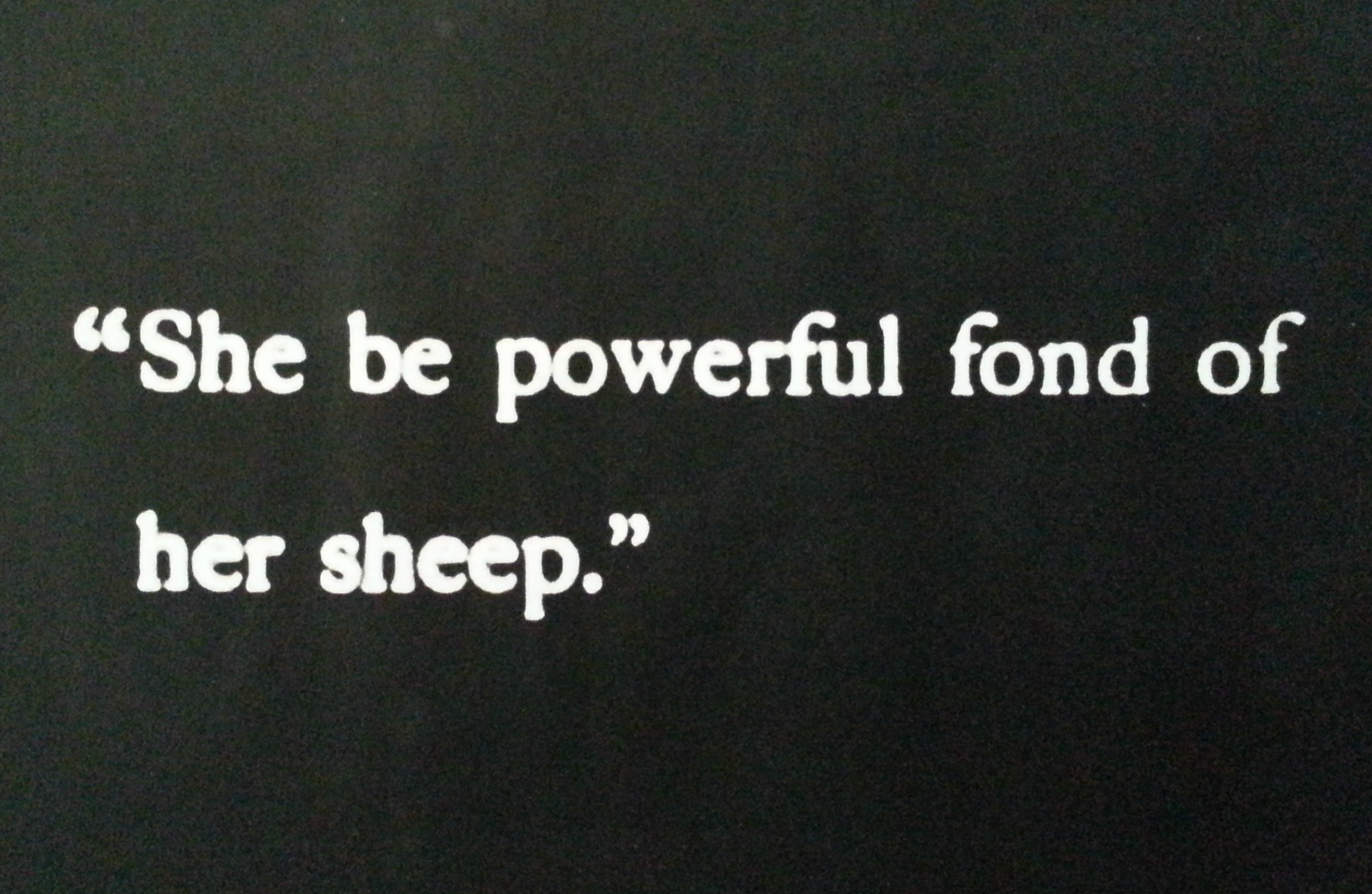

I love watching the film not only for its depiction of the quotidian (albeit staged) shepherding activities, but also because it uses some of my favourite local locations for the set. However, the constraint of being a silent, ‘three reeler’ film, with a run time of just fifty-five minutes means that much of the original character development is omitted.

If you are visiting Sussex you may stumble upon a rare showing of the film at Arundel Museum or Burpham Village Hall. If you don’t make it to a screening, you can view a few stills from the British Film Institute or look at the George Garland collection curated by West Sussex County Archives. Garland was a near contemporary of Tansy’s director Cecil Hepworth, and specialised in capturing rural scenes, crafts people and characters of Sussex from the 1920s to 1950s. I like to think that somewhere among the many pictures he took we may yet find a photograph of a ‘real-life Tansy’.

Alternatively, you can alight at Arundel railway station and walk the Downs to take in the film set locations using your own imagination. First published as an appendix to the book Sussex Pilgrimages, the essay ‘Arundel and Burpham’ written by Miss Betty Elllis sets out the route ‘for the wayfarer who wishes to follow in the steps of Tickner Edwardes’ charming story Tansy’. Modern readers can go online and read this blog and follow the trail if they cannot source Miss Ellis’ short but delightful essay:

https://www.alltrails.com/explore/recording/betty-ellis-s-1920s-burpham-stroll–2

After I had watched the film for the first time, I had to telephone David to let him know that I had seen it. It was then that David told me about a real life shepherdess who used to work the Sussex Downland farms in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. Her name was Ethel Oliver.

Ethel came from a long line of shepherds on her father’s side, and is known to have worked at Slindon, and later at Eartham with a celebrated Southdown flock of the same name. Until I started to put this article together I had hoped to be able to prove that Ethel was, as local legend has it, the inspiration for Tansy. I now know that this cannot be. Born in 1911, Ethel would have been just three years old at the time of the novel’s publication. The nostalgic part of me was initially disappointed to have found evidence to the contrary. However, those words from Tansy about a shepherdess on the South Downs being ‘almost unprecedented’ gives me hope that there may be more Sussex shepherdesses to rediscover, chronicle and celebrate.

I couldn’t end without sharing my favourite quote from the film:

Thanks to David, Frances, and Lynn for their help in researching this article.

Louise Spong is the founder of South Downs Yarn and produces woollen spun Southdown wool grown and dyed in the South Downs. You can visit her website at https://www.southdownsyarn.co.uk/ and you can find her on instagram as @louise_sdy and twitter as @SouthDownsYarn

: : : :

Sources used:

Tickner Edwardes, Edward, Tansy, (London, 1914)

Jerome, Peter, Eleven Sussex Books (Petworth: The Window Press, 2014)

Pictures and the Picturegoer, Volume 8, April – September 1915 http://archive.org/stream/pictureg08odha – page/246/mode/1up

Thurston Hopkins, Robert, Sussex Pilgrimages (London: Faber & Gwyer, 1927)

Sussex County Magazine, Volume VIII, No. 6, June 1934

Porter, Valerie. The Southdown Sheep, Singleton 1991

For information: There is a watermarked version of Tansy, which you can watch online at Huntley Archives